In Part 2 of our User Fee analysis, we learn the details that generated such strong opposition to the new tax. Read on for interviews with the council members who voted against it, as well as Morgantown’s police chief on why it has made him “ecstatic.”

Brief Recap

One year ago, Morgantown’s city council narrowly approved (by a vote of 4-3) the “Safe Streets & Safe Community Service Fee,” known more commonly as the “user fee.” Over the past year, everyone who works within Morgantown’s city limits has had $156 removed from their paychecks at a rate of $3/week. The money is split about 60—40 between the Department of Public Works and the Morgantown Police Department, respectively.

The Opposition

The user fee met strong opposition when it came up for a vote at Morgantown’s city council, with public comments against the new tax consuming more than an hour of the meeting. The three councilors who voted against the fee – Wes Nugent, Jay Redmond and Ron Bane – shared with Zackquill their own concerns about the levy, but each was sure to make one thing abundantly clear up front: they have no problem with nice roads or police officers. Their apprehension focused on finer details that are easy to miss for average citizens.

To start, there were concerns about fairness. Under the law, every person employed within the city is required to pay. But many major Morgantown employers are just outside the city limits. These include Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Mon General Hospital (though the city essentially surrounds the building), all of Suncrest Town Centre and Pierpont Centre, virtually every business along Mileground Road, all of the Morgantown Industrial Park, many student housing complexes, and all of Westover.

While employees in these locations are free from paying the taxes, they almost necessarily use many of the same streets to get to and from their jobs. Some of these businesses use the roads far more often than the average commuter for delivery, shuttle transportation, etc. Councilor Ron Bane points out that even the routes people use to get to work can cause inequity.

“For instance, let’s say you and I live right next to each other on Grand Street in Second Ward,” Mr. Bane said. “I work Downtown and you work in Cheat Lake. We both use the same roads, but I pay and you don’t. I’m not sure how to make it fair, but it’s a hard justification.”

There were also concerns that the fee is “regressive.” Regressive taxes are those that take a larger percentage from low-income earners than from high-income earners. (In the case of the user fee, $156/year, per worker, is harder for a poor family to pay than a wealthy family.) For instance, a full-time student who is supplementing their federal student aid by working 20 hours a week at $9/hour will lose almost a week’s paycheck every year to the fee.

$1 Million Extra

While the fee literally cut an estimated 100 years off the time required to repave the entire city, the councilors who voted against it also feel that the initial calculations could have been done better. The fee has generated almost $1 million more than the city could spend during its first year. Councilor Wes Nugent is pleased with the work that has been done so far (we’ll get to that in a moment), but feels uncomfortable taking more money than can be used from working people in a difficult West Virginia economy. Mr. Nugent just turned 40 years old, and his wife is expecting their second child. “I’m more interested in affordability in this city than I ever have been,” he told Zackquill last week. “I’m not making a lot, and my wife works at a day care center. The user fee for just my wife and I is $312 annually.”

Mr. Nugent points out that the city has also raised its fire fee, while the utility board raised fees to fund a new reservoir. “These are all laudable projects, but it doesn’t feel like it’s easy to adjust to all of them on a working person’s salary.”

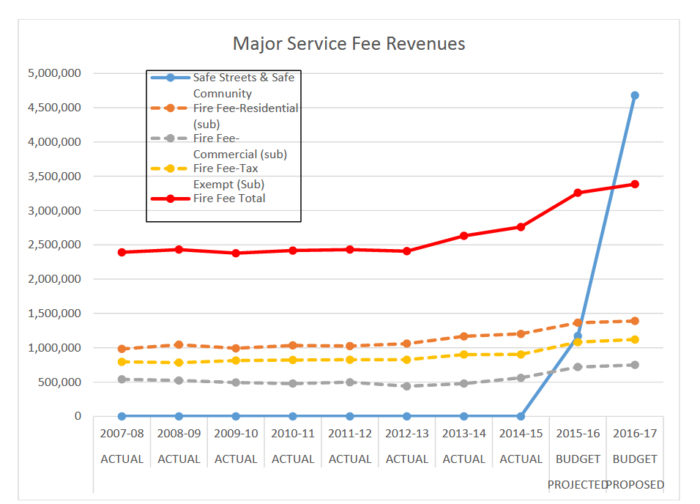

This graphic, prepared by the city, shows the comparative fees for Morgantown residents. The blue line which spikes in the 2016 and 2017 fiscal years represents the user fee, immediately surpassing the total revenue of the fire fee by more than 25%.

What Do We Get?

The first year that the user fee was in effect, the Department of Public Works has paved a little over eight miles of Morgantown roads. While this may not sound like much, it amounts to a total of 27 streets, some of which were longer than others. The city has also replaced (or inserted) 232 sidewalk ramps, which make the pedestrian walkways considerably more hospitable to wheelchairs and strollers. Public Works expects to repave another 10-12 miles of streets and an additional 120 sidewalk ramps this year.

Meanwhile, back at the Morgantown Police Department, Chief Preston could not be happier with the money that the user fee has brought in. “I am ecstatic, because we’ve been able to do things that we haven’t done before,” Chief Preston told Zackquill. He says that the department finally has 4WD vehicles, which also have stronger transmissions and suspensions than the old cruisers. He can finally put computer stations in those vehicles. (Until now, running license plates was still being done over the radio.) Officers now have tasers and batons, and are no longer forced to choose between a fistfight, pepper spray, and a gun. There are now body cameras equipped on patrols, which the Chief says protects both officers and citizens, while reducing citizen complaints.

The department has also hired seven new officers of its 130 original applicants. The process of getting them on the streets is long and involves many steps – a written test, physical fitness test, civil service review, background check, polygraph, psychological test, drug test, etc. By the time this article is released, those first seven officers will just be heading out on their own.

More controversial than hiring or purchasing equipment was the use of the fee to “retain” officers. This meant that all officers immediately got a $1.50/hr raise, with city council recently approving another $1.75/hr raise for 10-year veterans of the force. This means that the police department is now dependent on the user fee to maintain its force, making it unlikely that the fee will ever be reduced or eliminated. (Politicians can rarely afford to cast votes that cut the salaries of police officers.) On the contrary, the other four West Virginia cities with similar user fees have been consistently raising them over time, though Huntington recently had to fire 11 police officers anyway.

“When this money is used to supplement salaries, we’re planning essential staff around items not in the general budget,” councilor Bane said. “We’ve opened up Pandora’s box here. And if the current council stays in power, we’re also looking at a 1% sales tax.”

Here Comes the Election

As Morgantown figures out how to spend nearly $1 million more on roads and police, debate about the user fee continues to stir. The ongoing discussion may make the issue of local taxation an important issue in the upcoming city council elections, when local residents just might spot a new police SUV driving newly repaved city streets on their way to the voting booth.

–

Click to view PART 1.